Young Naga Warrior at New Year Festival by JOANNA MACLEAN

JOANNA MACLEAN INTERVIEW

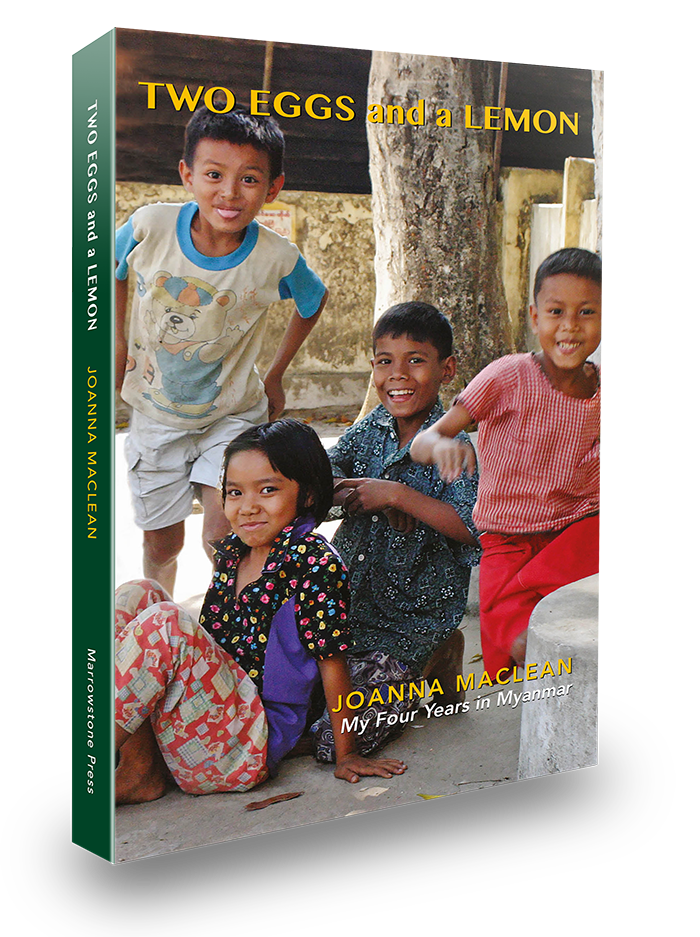

GG: In your time with the Red Cross, you’ve traveled extensively, engaging in the politics and cultures in many countries. Your book, Two Eggs and a Lemon, chronicles the four years of your last posting in the country of Myanmar. What were your official duties there as Head of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies’ Delegation?

JM: Our IFRC Delegation’s function was to act as advisor and supporter of the Myanmar Red Cross Society (MRCS), to strengthen its infrastructure, capacity, and outreach, to garner international funds and to foster stronger programs within the country. As our organization is ‘a federation of all National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies’, we must respect the role of a national society within its own country and cannot dictate or decide what they do. We can offer advice, suggest changes, propose new programmes but ultimately the decisions and actions remain the responsibility the National Society. Both diplomacy and patience are always necessary.

Being a bridge between MRCS (The Red Cross Myanmar Society) and donor National Societies and organisations, I held two roles; I was ‘protector’ of the MRCS. I defended and explained its actions and its role within the complex political and social situation.

And I was ‘promoter’ of the MRCS, forging new donor relationships, presenting the on-going health and welfare, disaster preparedness, and response programs, as well as helping others understand the sometimes extreme difficulties under which the MRCS was working.

The job also involved leading my team of international delegates, each of whom had a particular expertise in program development, disaster response, health, organizational management, and finance . We were ably assisted by our local staff, several of whom had many years of experience and could help us maneuver through the often convoluted ways of administration and decision making, and advise us on culturally acceptable ways of operating.

In spite of the many challenges and frustrations we faced together, my four years in this position as Head of the IFRC Delegation in Myanmar was extraordinarily interesting and satisfying, and I continue to follow and support the MRCS, however I can.

GG: When you arrived, did you feel the political tide shifting and was there a detectable sense of collective hope within the people that something long lost, something necessary for the human spirit, was returning?

JM: I remember meeting with some ‘old-time’ foreigners in one of the hotels when I was first in Yangon. Listening to their invaluable stories, I learned a lot. But what stayed with me was what they and every new group of visitors to the country believed: That ‘this’ year, be it 1997 or 2002 or whenever they happened to be there, would be the year the country opened up. I’m not sure this was because they truly perceived something was changing or that they just wanted to be the ones to witness then proclaim the country’s new direction.

In talking with my staff and colleagues of the Myanmar Red Cross and other locals, we saw less optimism and more reality; they and their families were the ones who had to live through a long, difficult period in the country’s history. However, I was always impressed that the Myanmar people managed to maintain their sense of humour, and remain stoic and courageous even when their freedom and opportunities were severely curtailed. Against all the odds, most did indeed manage to maintain their dignity and spirit, and their quest for knowledge. Their generosity to others was remarkable.

In my first year, in 2002, there was a brief period when Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest, and she travelled in several of the regions before being arrested again, clearly, from trumped up charges following an altercation between her small cavalcade and some local protesters. It was most likely staged. There was a darkening of the mood in the country after a short interlude of hope. And through all the time I was there, the rumours and stories that circulated, were refuted, then would appear again in another form. The spirit of the people vacillated, dimming then growing bright, again and again, often weak, at times stronger, but always at the core was hope.

Stall holder at Kengtung Market, Shan State by JOANNA MACLEAN

GG: There’s a lovely bit of unexpected joy when the reader comes upon the title chapter of your book, ‘Two Eggs and a Lemon.’ After reading it, I was reminded of the last few pages of Lewis Hyde’s extraordinary book, The Gift, when he offers a closing story by Pablo Neruda. The Chilean poet recounts a moment in his childhood, standing by an old fence in his back yard: “through a hole in a fence board, a hand all of a sudden appeared—a tiny hand of a boy about my own age. By the time I came close again, the hand was gone, and in its place was a marvelous white toy sheep. The sheep’s wool was faded. Its wheels had escaped. All of this only made it more authentic. I had never seen such a wonderful sheep. I looked back through the hole, but the boy had disappeared. I went into the house and brought out a treasure of my own: a pine cone, opened, full of odor and resin, which I adored. I set it down in the same spot and went off with the sheep…I never saw the hand or the boy again. And I have never seen a sheep like that either…Maybe it was nothing but a game two boys played who didn’t know each other and who wanted to pass to the other some good things of life. Yet maybe this small exchange of gifts remained inside me also, deep and indestructible, giving my poetry light…to feel the intimacy of brothers is a marvelous thing in life. To feel the love of people of whom we love is a fire that feeds our life. But to feel the affection that comes from those whom we do not know, from those unknown to us, who are watching over our sleep and solitude, over our dangers and our weaknesses—that is something still greater and more beautiful because it widens out the boundaries of our being, and unites all living things.”

This exchange you describe in Chapter Thirteen, as well as many other chapters in the book, speaks profoundly about the joy of ‘gift exchange’ as a way to widen our understanding of people and their culture. At what point did you realize this experience would be the title of your book? How has it affected you as you continue to travel throughout the world and what can we expect next?

JM: My initial plan was to work on a photo book about Myanmar, focusing on the people and places that had touched me, adding some short stories and information inserts to make it more interesting. With this in mind, I joined a week-long writing course in Chiang Mai to learn how I could make this idea come to fruition. During the course, we were expected to produce short pieces—from memory, from life, from our imaginations, from a starting point of an introductory phrase—and I found that I enjoyed the process and discipline of writing. My previous experience had been mainly writing things like project proposals, reports, and campaign strategies for my work in the Red Cross.

Smiling girl at Naga New Year Festival by JOANNA MACLEAN

Our tutor and some of the group encouraged me to think of writing my experiences rather than doing a photo book. I was not convinced, but little by little that seed planted in my brain began to grow. Soon after the course ended, one morning, with my computer on my knee, I started thinking about all the experiences I’d had during my stay in Myanmar. My first memory came from that evening when I received a precious gift of two simple objects from a child. I wrote a sentence off the top of my head and gave it the heading ‘Two eggs and a lemon.’ I filed it and started another document. I was on a roll. Within that day, I started 28 short stories that subsequently became the chapters of my book.

After the course, a small group of us met every fortnight to share and critique each other’s writing. I first shared with them the chapter about my neighbourhood, the one I’d entitled ‘Two eggs and a Lemon.’ I prepared two versions –the first had only text, the second, I added photographs. I was sure they would like the second version best. But they didn’t; they preferred just reading the story. They didn’t want to be distracted by the photos. It was then I decided to ‘write’ the book rather than presenting a photographic journal. Interestingly enough, the photo I chose to head the chapter, is the one that became the cover image for Two Eggs And A Lemon.

Still, my original idea of a photographic journal didn’t go away. It’s become my next project on which I’m currently working—portraits of Myanmar and the people people I encountered during my stay there.

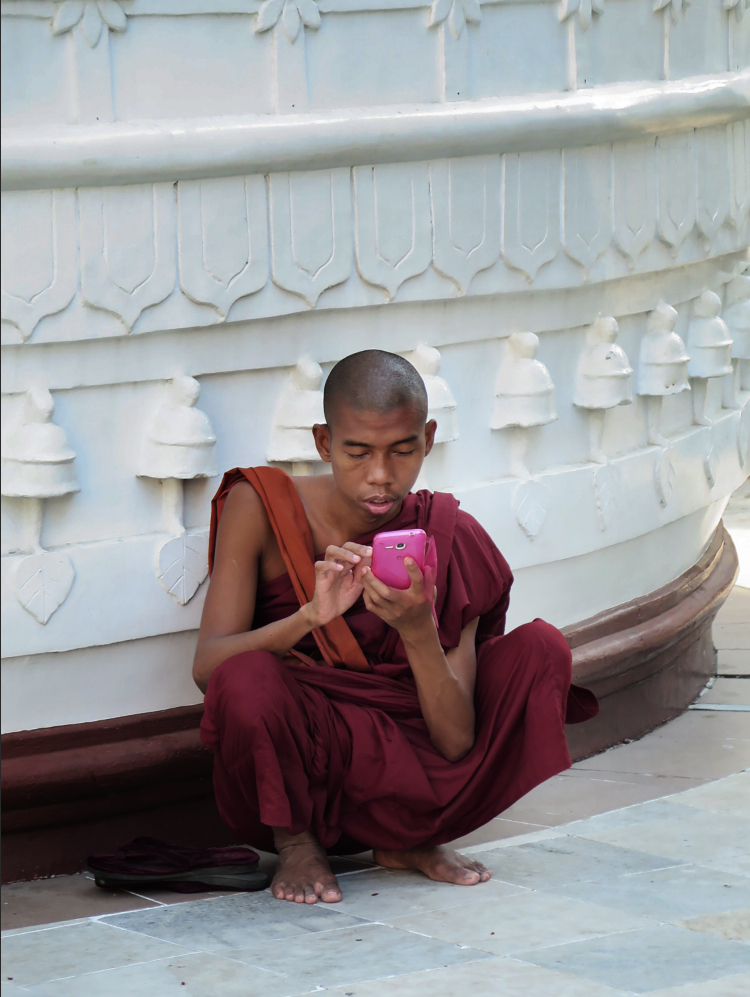

Monk studies his phone at a temple by JOANNA MACLEAN

![]()

Joanna is currently working on her next book featuring photographs and text

about the people of Myanmar.

![]()

Her most recent publication is

published in 2016.

ADD THIS BOOK TO YOUR LIBRARY.