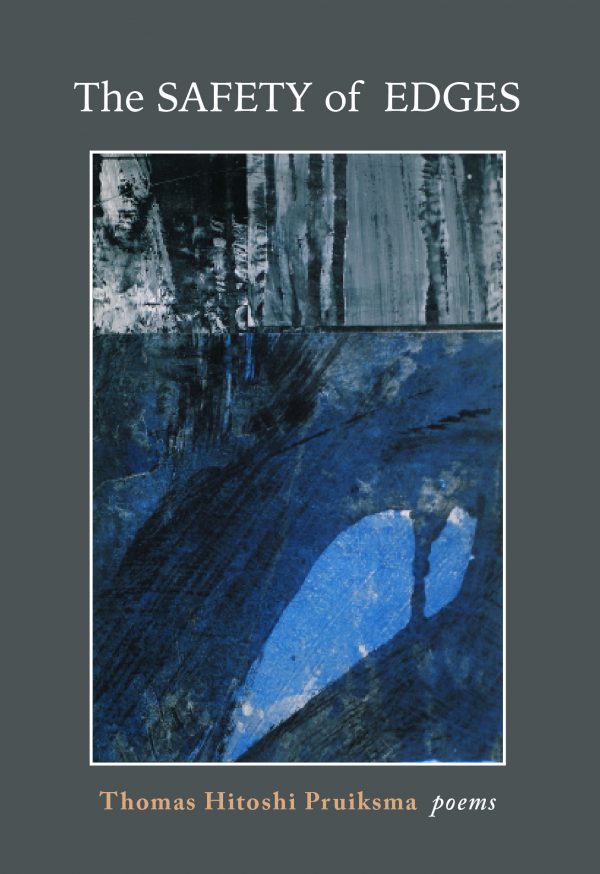

![]() An interview with Thomas Hitoshi Pruiksma

An interview with Thomas Hitoshi Pruiksma

GG: I find the title, The Safety of Edges, alluringly enigmatic. How did it come into being?

THP: During the time I was writing many of these poems, I often found myself remembering the experience of walking through my first home in the dark, finding my way by memory and by reaching out to the objects around me—the corners of doorways, the backs of chairs, the edges of our family hutch. This remembering led to two poems written on consecutive days, one of which is the opening poem of the book, “Insight,” and the other of which I ended up setting aside. “The safety of edges” was a line from that second poem, so even though the poem isn’t part of the collection, the insight it offered remains, like a table in the dark known only by its closest edge.

GG: Thomas, your avenues of expression are many and multi-dimensional—translation, poetry, music, theater, magic—and it feels or seems as if the shape of the word, the space of it, is the thread holding together this curiously fascinating necklace. On May 9th, 2018, you and I met for the first time at a memorial for the American poet, essayist, translator, Co-Founder, and Editor of Copper Canyon Press, Sam Hamill. Sam had emailed me several months earlier asking me to attend what would have been his 75th birthday. Unfortunately, he died before I arrived from Thailand. It was an altogether different kind of event, but still, a celebration. How did your life intersect with Sam? What were the circumstances that brought you two together?

THP: First, thank you for what you said about the shape of the word. I’d never thought to put it that way, but reading it—hearing it in my inner ear—it feels right to me. I do wish to honor the fullest possibilities of the word, both the shape and the space of the word.

Whenever I hear the phrase “the word” I think of the way my friends in Mexico speak of la palabra, “the word,” whereas in North America and in English we tend to think of “words” rather than “the word.” But there is something powerful and singular about thinking of words as “the word.” It has to do with remembering that beneath the multiplicity of our words, beneath all the ways that we express ourselves through words, there lies something deeply common, deeply human, and deeply able to hold both singularity and multiplicity in the same breath.

I first met Sam in 2005 in Vancouver, B.C. It was February. I’d gone to a big writing conference as a kind of anthropologist, not feeling at home in the hubbub but curious to see what the fuss was all about. On a whim, through a friend, I gave Sam some translations I had done from the 12th century Tamil woman, poet, and saint Avvaiyar, and Sam, to my surprise, not only read them and liked them, but also invited me to lunch. As soon as our schedules coincided, I went to visit him in Port Townsend at Kage-an, his “shadow hermitage.” We had a wonderful conversation and meal, and he surprised me again by suggesting that he print a letterpress edition of Avvaiyar’s poems. So I got to work translating enough of her poems to be able to put together a small chapbook. We would meet whenever I was able to visit, and we eventually decided it would be better to bring out the poems in a trade edition through Red Hen Press, which is how Give, Eat, and Live: Poems of Avvaiyar came into being and into print.

In the thirteen years we knew each other, Sam went from being an editor and mentor to being a fellow writer and friend. He introduced me to the work of poets I might not otherwise have encountered, and also shared with me his love of sake, the blues, and country western music. Most important, he gave me a living connection to people and poets who have been very important to me, both those I knew or met personally, like Hayden Carruth and W.S. Merwin, and those I was never able to meet, like Denise Levertov.

GG: I’m sure you’re familiar with the large mural at SeaTac by the late Michael Fajans called Highwire, of which he writes, “Travelers [having flown by plane] retain, for a short time, the aura of having done something superhuman. The traveler has defied the intuitive laws of time, biology, and physics. He or she has moved, for want of a better term, magically.” There seems to be, in much of your poetry, a wonderful dichotomy of what is, what isn’t, what could be. What is this magnet between words and magic you hold?

THP: I’ve long enjoyed looking at Fajans’s mural, which so delightfully evokes the golden era of stage magic at the same time that it connects it to our experience of traveling by plane. I particularly appreciate how you can’t take in the entire mural in one glance, but rather must walk alongside it to see the larger story it suggests. Which is similar to what happens when reading or hearing a poem. One can’t take it in instantaneously, but rather has to travel through each of its lines to have a sense for the larger whole which then appears, and can only appear, in our memory and imagination.

I’ve always been fascinated by the edge of possibility. It’s what drew me to magic as a child, and also to the study of philosophy, language, and poetry. Over and over my experience returns me to how fundamental it is to live with a wide sense of possibility. A feel for how what is, what isn’t, and what could be are far more interrelated than they may at first seem. And that between seeming and being lies the entire play of life, which we glimpse only in part, as a fleeting moment on a stage or a bit of music captured in words.

GG: An underlying theme of the interviews I’ve done these last few years touches on why art matters and why it should—to you, poet and musician, to the man next door who loves to cook, the woman who manages the local bank, the policeman, politician, the monk, and medical technician, the bartender, and young child. What takes shape in your mind when you think about what you do as an artist, what it means for yourself, for them? Is it an illusionary device or is it something far more, perhaps some a priori gift to keep us, at best, curious, and, at worst, from complete annihilation?

THP: In thinking about this question, as I have for a long time, I’ve been guided by my friend Wendell Berry, and through Wendell, by Ananda Coomaraswamy. As both Berry and Coomaraswamy have taken pains to articulate, before anything else art is a way of making. It is by art that a cook transforms ingredients into convivial sustenance, by art that a manager fosters harmony among her colleagues.

And so one of the things that I hope my work as an artist may do is inspire people of all kinds to new artistry in their own realms. The attention that art requires, both in its making and its reception, allows new possibilities to enter the world.

I think this is all the more important because of the great predicament we now find ourselves in, both ecologically and culturally. We are suffering the ill effects of work done without art, speech spoken without reverence or music. Our life is a miracle and a gift, and we can only honor it by giving of ourselves through those arts which are naturally our own. Otherwise we do indeed face the prospect of annihilation, within ourselves and without alike.