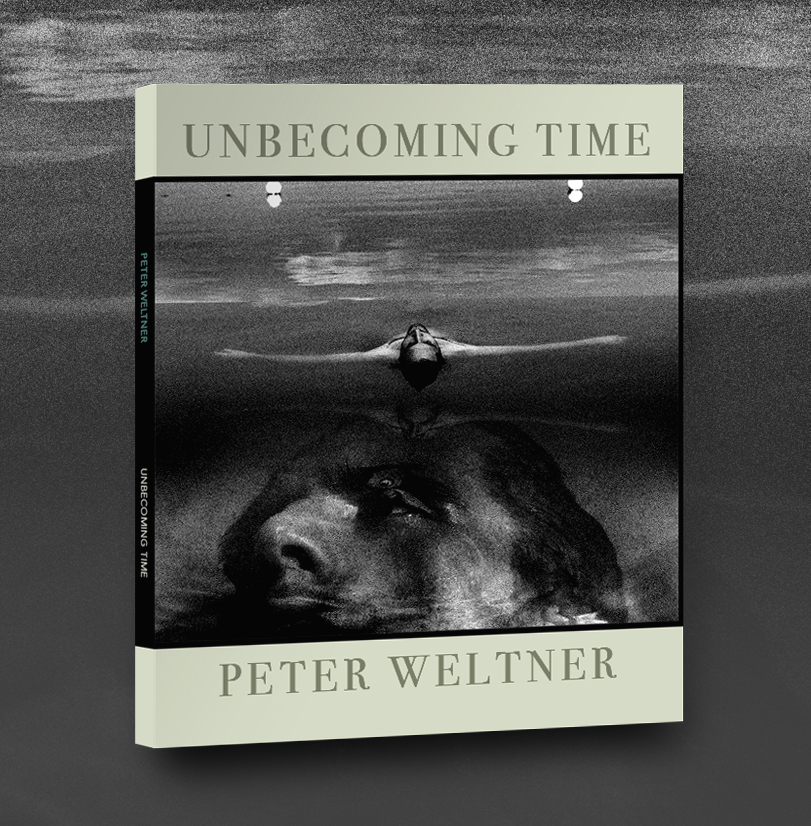

Heidegger extolled language as the “house of being” but Peter Weltner in this exquisite and deeply moving new collection finds it “betrayed by lies spouted each moment in every known tongue.” Daring “to be ceremonial” in face of our constitutive dishonesty, Weltner’s poetic craft is revelatory, allowing the singular things of the world to show themselves. Weltner’s temporal horizon is “unbecoming” in two ways. On the one hand, it is the wistful, implacable, and often elegiac flow of time—“Most of the men I knew then have died. Every day I think of them.” And “Why must I leave you, the earth I love?” as even “memory’s streams” are “fated to flow seaward.” On the other hand, these poems enact a powerful unbecoming of time, momentarily halting its flow so that the silent preciousness of the past becomes audible. These are compassionate, appreciative yet doleful epiphanies in which the grace of what has been comes forth as it is also slipping away. “One last, uncertain glimpse of earth is all I ask from dying: to leave the life I love, forgiven and forgiving.” This is a book to help us with our living and dying in a time of seemingly endless chatter.

Jason M. Wirth, Professor of Philosophy, Seattle University,

Something Understood

When I was a boy, funerals were no place

for children. I was left at home to play

with friends. First grandmother Karen

died, then Louise. Gone, leaving no trace,

as if one day they’d vanished. I’d pray

they’d return to me. Fruitless prayers, barren

hopes. I stand on a hill of Bay View Cemetery

in Jersey City, a park, docks, the Hudson

below me. It’s not what we ask of the dead

but what they ask of us that makes

us who we are. The river enters the sea,

emptying into it, as if its life were done

as ours must be at the end, having said

what we could. Cargo ships, a cruise liner

plow into the North Atlantic. To suffer

departure. What an ocean gives, it takes

back. I’m watching its heedless flowing,

feeling the tides, the currents of my dying

inside me, the emptiness of it, my life bidden

to it. Not mine but my father’s. “My son, my son.”

Peter Weltner, from Unbecoming Time